The Supermarine Spitfire was a single-seater fighter plane, one of the most important aircraft of the Second World War (1939-45). Employed by the Royal Air Force in such crucial encounters as the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940, the Spitfire gained legendary status thanks to its graceful lines and superlative manoeuvrability.

Design

In the pre-war years, the Royal Air Force (RAF) remained preoccupied with biplanes, but designer Reginald J. Mitchell came up with a new concept, the Spitfire single-seat monoplane with distinctive elliptical wings. It was also armed with eight machine guns and so could certainly spit fire. The company that built these supermodern machines was Supermarine, a firm that had already won three Schneider Trophies, the annual prize for the fastest seaplane in the world. Supermarine was owned by the giant armaments firm Vickers Armstrong and was able to secure powerful new engines from Rolls Royce.

A Spitfire prototype was built in January 1935, and the first flying model appeared in March 1936. The first test pilot was impressed and stated as he climbed out of the plane, "Don't touch anything" (Saunders, 15). The first operational planes were coming off the production line by May 1938. The delay in production highlighted the need to diversify the building process, and the Morris car company was approached to ensure the new fighter could be mass-produced quickly enough to meet the growing threat from Nazi Germany. 1,000 Spitfires were ordered, then the largest-ever aircraft contract in Britain's history.

Not a few upgrades were soon made such as fitting machine guns and a cannon in each wing, making the windscreen bulletproof, and adding armour plating around the engine. By 1939, one Spitfire found itself in the French Air Force, but such was its performance and manoeuvrability, the fighter was eventually used by many countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Greece, Turkey, Egypt, and the USSR. A raging success, the Spitfire was the only Allied fighter to be continuously manufactured throughout WWII, and the RAF alone operated over 20,000 of the fighters between 1938 and 1947. There was even a naval version with folding wings, which was built for use on aircraft carriers and was called the Supermarine Seafire.

Specifications

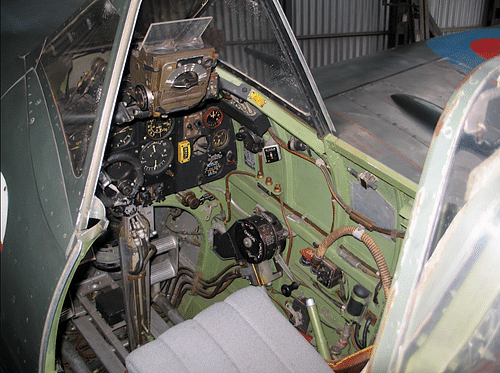

The Spitfire had a total length of 29 ft 11 in (9.12 m) and a wingspan of 36 ft 10 in (11.23 m). Constantly updated through its years of war service, the specifications of the Spitfire varied across 24 models, with capabilities depending not only on design tweaks but also on armament configuration and the altitude flown at. Most Spitfires had a Rolls-Royce Merlin supercharged V12 engine, like the Lancaster bomber, Hawker Hurricane (the RAF's second-choice fighter), and American P-51 Mustang. The Mark XIV Spitfire was given an even more powerful Rolls-Royce Griffon V12 engine capable of 2,050 hp (1529 kW). The Spitfire's maximum speed was 448 mph (721 km/h), although something around 350 mph (563 km/h) was more usual. The maximum operational altitude was around 35,000 ft (10,668 m), although later versions could reach up to 43,000 ft (13,105 m). The Rolls-Royce engines were a crucial factor in performance: "It seemed that Merlins could withstand any amount of abuse. It was one of the few engines that could tolerate full power loads for long periods" (Cawthorne, 140). The undercarriage was retractable, which greatly increased the aerodynamics, but this innovation for British planes caused many a pilot to forget to put the wheels down, and so they not infrequently performed a "belly-landing" to the horror of squadron leaders.

The initial armament was eight (0.303 in / 7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, but these evolved into a standard two machine guns (0.5 in / 12.7 mm) and two Hispano cannons (0.8 in / 20 mm) in each wing (although there were other variations, too). The Spitfire carried ammunition drums of 300 or 350 rounds for each machine gun, which meant that in reality, a pilot could only fire these for a total of 14 to 15 seconds (a German Me 109 could fire for 55 seconds). On the other hand, a three-second burst would fire 60 rounds per gun, so all four firing could plough 240 bullets into a target in a short burst, which was usually aimed under the enemy aircraft as the fighter approached from below. The canons fired at a much slower rate and had 60 shells each (later doubled to 120). The 0.303 bullets could pass through non-vital areas of a bomber and do little harm, but a cannon shell left a hole the size of a fist and so was much more effective against larger planes. Pilots had illuminated gun sights positioned in front of the lower part of the windscreen, which could be adjusted depending on the wingspan of the enemy plane.

The Spitfire was designed as a fighter, but it could also carry a single 500-lb (227 kg) bomb or two 250-lb bombs or rockets fired from launchers fixed under the wings. The normal range of a Spitfire was around 575 miles (925 km). An extra fuel tank could be fitted to each wing and under the fuselage for long-range missions, adding an extra 100 gallons (420 litres) of fuel or more. Some later Spitfires had their distinctive wing tips clipped to a straight edge, which improved their ability to roll.

The plane's colour scheme varied depending on location. For Europe, a light blue undercarriage and dark green-brown camouflage on the upper part was common while in desert warfare the camouflage scheme was yellow and brown.

Operations

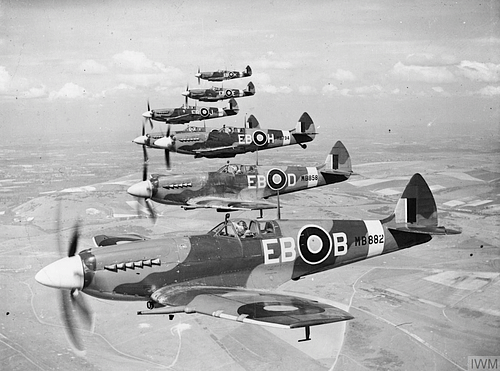

The first Spitfire squadron was formed in July-August 1938, No. 19 Squadron based at Duxford; more quickly followed. The standard squadron had 12 Spitfires. Arranged in groups of three, they flew sorties over the Continent, but their range was limited. The first enemy planes to be shot down in British air space, two German bombers over Scotland, were victims of a Spitfire attack on 16 October 1939. Spitfires were stationed in France at the beginning of the war but were withdrawn after the debacle of the Dunkirk retreat in May-June 1940. Fighters desperately tried to protect the evacuation fleet – 106 fighters were lost; of these, 67 were Spitfires. The RAF now had to regroup and prepare for a German invasion of Britain, an attack that would be preceded by a bombing campaign.

Sandy Johnstone, then a Flight Lieutenant, describes flying a Spitfire hunting enemy bombers over Britain:

As the twelve Spitfires manoeuvred into formation, and climbed for the east, I glanced down at my watch. Under ninety seconds. Not bad…I started to wonder if we'd be too late again…I had to start thinking tactics, we should really add a couple of thousand feet to our directed height, better to be a little too high than caught in the murderous fire raining down from the 109s…Simmering in the morning sun, wave upon wave of bombers, driving for London. Stepped above and behind, the serried ranks of Messerschmitts. Covering mile upon mile of sky, as far as the eye could see. It was at once magnificent and terrible. (Cawthorne, 25).

Another pilot, Group Captain Adolph "Sailor" Malan, who was the top RAF ace of 1940, wrote down the following rules for new pilots, a list which was distributed by Fighter Command and so was often found tacked to the wall of fighter mess halls:

- Wait until you see the whites of their eyes. Fire short bursts of one or two seconds and only when your sights are definitely "on".

- While shooting think of nothing else, brace the whole body, have both hands on the stick, concentrate on your ring sight.

- Always keep a sharp lookout. "Keep your finger out".

- Height gives you the initiative.

- Always turn and face the attack.

- Make your decisions promptly. It is better to act quickly even though your tactics are not the best.

- Never fly straight and level for more than 30 seconds in the combat area.

- When diving to attack always leave a proportion of your formation above to act as a top guard.

- INITIATIVE, AGGRESSION, AIR DISCIPLINE and TEAMWORK are words that MEAN something in air fighting.

- Go in quickly - Punch hard - Get out.

(Cawthorne, 35)

The fighter plane, still being developed in response to active use, would become crucial to the defence of Britain, taking on enemy fighters and providing escort for RAF bombers going the other direction. Spitfires were also used as fighter-bombers. When fitted with two vertical cameras, Spitfires could be used as long-range reconnaissance aircraft. There was also a version with a pressurised cabin that could operate at high altitudes, useful for tracking high-altitude bombers and weather patterns. During WWII, Spitfires saw service in the Mediterranean, northern Europe, Italy, North Africa, the Middle East, Malaya, Burma, and the Pacific. Of all these theatres of war, one in particular would secure the Spitfire's iconic status: the skies over Britain.

Battle of Britain

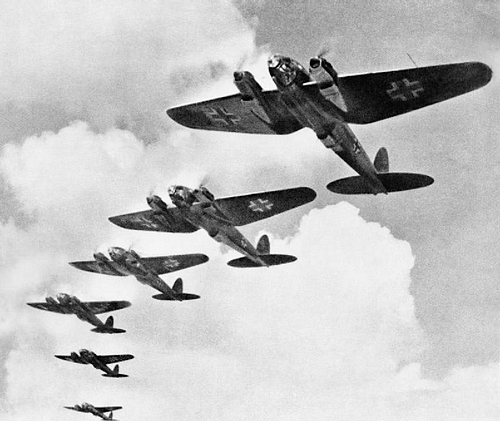

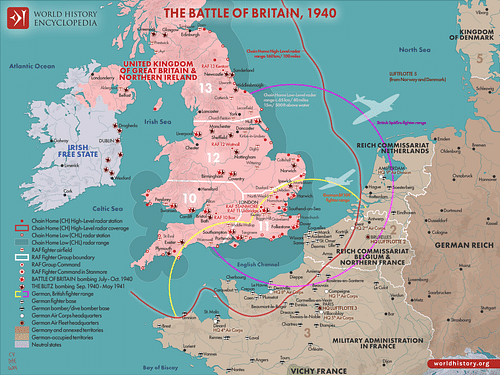

After the fall of France, Adolf Hitler turned his attention to invading Britain (Operation Sea Lion), but first, he would have to secure the skies and free them from the enemy planes which would wreak havoc on any invasion force crossing the English Channel. So began what became known as the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940, officially dated as 10 July to 31 October by the Air Ministry.

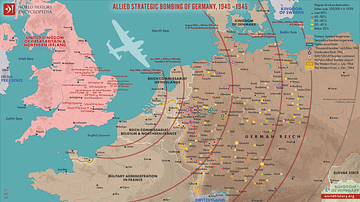

At the start of the Battle of Britain, the RAF had just 19 Spitfire squadrons. The combined number of Spitfires and Hurricanes was 331, although many more aircraft were in production. The Luftwaffe (German Air Force) was numerically far superior to the RAF, now in desperate need of more pilots as well as more planes. Home advantage was an important factor since the German fighters had far less time in the skies above Britain before their fuel ran out. Another advantage was that German pilots obliged to bail out and use their parachutes, if they survived, became prisoners of war. This was a battle where men were just as vital as machines, and training pilots and replacing losses became problematic for both sides. Another British advantage was radar, which communicated to fighter squadrons approximately when and where German planes were flying. The Observer Corps, a volunteer group, took over from radar when the planes passed the electronic listening stations.

The Luftwaffe, because of the production emphasis on dive bombers, lacked the heavy bombers needed to really obliterate strategic targets such as airfields. On the other side, a bomber could withstand a great deal of punishment from the small calibre machine guns of fighter planes. It was also true that because it took the British fighters up to 20 minutes to assemble and reach the necessary altitude, the German escort fighters were often ready and waiting for them. The battle would be finely balanced with both sides never entirely sure of their enemy's losses.

To ensure as many planes as possible could be put into battle, there began the Spitfire Fund campaign, which called for civilians to give what they could. The campaign called for £5,000 to fund a Spitfire (they actually cost around £12,000 each). People responded, townsfolk got together, Boy Scouts raised funds by doing odd jobs, local newspapers ran subscription campaigns, and collection tins were rattled in offices, pubs, and churches. Lord Beaverbrook, head of the Ministry for Aircraft Production, was behind the scheme, and he was utterly ruthless in getting more aircraft made as quickly as possible. Paperwork was eliminated, production problems immediately dealt with, and labour rules ignored so that by June 1940, 300 aircraft were being built each week, and 250 damaged ones were repaired back into service (a crucial statistic since up to 30% of planes were damaged by accidents as opposed to enemy fire). To guard against destruction by enemy bombers, Spitfire factories were dispersed throughout Britain.

The Spitfire was more manoeuvrable than its main German fighter rival the Messerschmitt Bf 109 (aka Me 109E), but the latter could dive better thanks to its fuel-injection engine. Both planes had a similar top speed. The German fighter had a better firing range, but the Spitfire could fire its armaments in a more concentrated fire of bullets (at the right distance from the target). The two planes were evenly matched at the outset, but crucially, the Spitfire was continuously improved with design tweaks as the intense air battle progressed, such as a better cooling system for the engines which tended to overheat. The second fighter of the RAF was the Hawker Hurricane, slower than the Spitfire and Me 109E but a reliable aircraft. Much to the chagrin of pilots, there were many more Hurricanes than Spitfires available. In the latter stages of the Battle of Britain, Spitfires and Hurricanes were used as a single tactical unit of 60 aircraft, a formation known as a 'Big Wing'. These fighters, as all fighters, were ordered to prioritise hitting the bombers.

The Luftwaffe could attack from bases across the Channel and in Scandinavia. The Germans also kept the British guessing by continuously switching targets such as Channel shipping, coastal towns, airfields, radar stations, and London. In the end, RAF fighter pilots, who included many from the Empire nations and allies such as Poland and France, fought off the Luftwaffe threat, whose losses became unsustainable. The RAF had won the Battle of Britain, and the Spitfire entered legendary status. The RAF's total aircraft losses were around 788 compared to the Luftwaffe's 1,294 (Dear, 127). By October, the Germans changed strategy again and focussed on the nighttime bombing of cities, a heavy blow for civilians but strategically a much less important target. The Luftwaffe's decision ensured that the RAF maintained air superiority. Operation Sea Lion was abandoned. This new phase of the war included the London Blitz, but many other cities suffered too, as did German ones as the RAF retaliated in kind. Suddenly, the Western Front had changed from a conflict involving relatively few highly trained military specialists to one involving hundreds of thousands of civilians.

In the Battle of Britain, Spitfires shot down 529 enemy aircraft while 361 Spitfires were lost (Saunders, 27). Crucially, the RAF ended the battle stronger overall than it had started in terms of planes and pilots available. The Luftwaffe more or less maintained its strength, but it had lost many of its best pilots, a result which had consequences for Germany's subsequent attack on Russia in Operation Barbarossa in June 1941.

Legacy

The Spitfires continued in service, but their short range limited their role in Europe until after D-day in June 1944 when they could begin to fly from bases in France again. The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine fitted to Mark IX Spitfires was fitted to the P-51 Mustang, the American plane that, thanks to the greater altitude the engine permitted and its superior range, changed air warfare from 1944. The RAF's last operational Spitfires were withdrawn from service in 1954.

The Spitfire, largely because of its crucial role in the Battle of Britain, has gained iconic status. Surely, no other model plane has adorned children's bedrooms in greater numbers. The Spitfire, with its speed and grace of line, remains a star performer at air shows worldwide thanks to the 50 or so examples still flying, and various museums have Spitfires on permanent display, notably the Imperial War Museum and Science Museum, both in London, the city the plane did so much to defend.